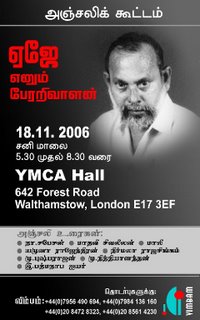

Shanmugalingam: Jaffna’s applied dramatist

I am really pleased to have been asked to write this short article on the playwright K.M. Shanmugalingam. He is a man who is well known to the Sri Lankan Tamil theatre community but he is less familiar to audiences in the wider Sri Lanka and certainly comparatively unknown here in the UK. His contribution to theatre spans more than 30 years covering a tumultuous period of Sri Lankan history. He is famed for a range of plays not least the seminal Mann Sumantha Meniyar (Sons of the Soil). This play first staged in February 1985 is a pivotal moment in the development of Sri Lankan Tamil theatre and many of the Tamil theatre practitioners I have met in the last 7 years were either directly involved in this production or remember it as a profound inspiration. However, it is not my place to offer analysis of these plays, as there are many far more qualified than myself. I want instead to mention three encounters I have had with Shanmugalingam to give my perspective, as a British theatre practitioner and academic, on the nature of his contribution to Sri Lanka culture and theatre.

These three encounters have happened at very different times. One was in January 2000 in Jaffna when the situation was very tense and the LTTE were soon to make their push through Elephant pass. The second was in the ceasefire period during a workshop at the University of Jaffna Theatre Studies Department and the third is part of ongoing discussions about the notion of applied theatre and its relevance to the theatre community in Jaffna.

The meeting in January 2000 was the first time I met Shanmugalingam and we talked with some other theatre colleagues in his house in Jaffna. We sat in the dark with a kerosene lamp allowing me to pick him out just in front of me. His tales of his involvement in Jaffna theatre and his eloquent advocacy of the importance of the practice of theatre in historically difficult times made for fascinating listening. I was introduced to a man whose understanding of theatre was closely tied to his sense of his role as an artist in this community. This was not a singular and closed vision but one that was adaptive to the possibilities and constraints of different time periods. His full length plays acutely tied to the moment such as Mann Sumantha Meniyar were complemented by his commitment to children’s theatre as a place were theatre could flourish within the obvious confines of the conflict. His understanding of the relationship between theatre and its context was my lasting impression of this meeting and it was most clearly demonstrated in his aside at one point of the discussion. He commented that his wife, who was present at the conversation, would love them to go to live outside Jaffna with their children abroad, but he felt he could not leave. It is not for me to praise those that stay or condemn people who choose to move from Jaffna, as these are of course difficult personal decisions, but there was a sense that Shanmugalingam was expressing his need to stay connected to a place. This was where his art arose from – and it would be impossible for him to be separated from it. He seemed to emphasise an important lesson for those studying artists such as Shanmugalingam as well as other playwrights. Their work is only understandable when it is seen to be embedded in a moment – and its significance can only be revealed by an analysis of the place and time in which it emerged. Shanmugalingam proved this but also lived it in his desire to stay rooted to his home in Jaffna. In the dark of his house, at a difficult moment in Jaffna history, this conviction and commitment demonstrated how his art and his life were indissoluble.

My second point is linked to this example and comes from a workshop that I was running for Jaffna university Drama students in 2002. Here the emphasis is on links between language, culture and education and how the playwright can intricately tie these three concerns together. I was speaking to the University students and Shanmugalingam was translating for me. One student asked a question in Tamil that contained a commonly used English word. Shanmugalingam’s translation into English reversed the process and he gave me the question in English but with the English word rendered in Tamil. The students laughed and his point was made. In a gentle way he illustrated the influence of English on the Tamil language and how it was possible to gently resist the excesses of that process. This was not done in a didactic, aggressive or arrogant way, but with a humorous act of language play that revealed to the original student questioner what she had done. Again this simple act revealed to me something of the nature of Shanmugalingam the playwright. A profound attention to the importance of words, and a particular commitment to the Tamil language, was exercised through a play with words that entertained as it taught. This small incident seemed to indicate both his commitment to language and to education – and having subsequently seen performances of his plays in schools, I have witnessed this example magnified in his cultural and educational programmes for children. Again this exemplifies what theatre does best – it develops a profound respect for one’s culture, language and the dilemmas facing one’s community through a medium that teaches through play rather than the stick. Shanmugalingam did not flinch as his made his reverse translation and pretended innocence to what he had done even though the students laughed. His small word play, a tiny moment of theatre, illustrated how serious theatre can be.

My final point links both Shanmugalingam’s commitment to remaining in Jaffna and his interest in education. It concerns his misgivings with the notion of applied theatre as it became used within and outside the theatre communities in the north of Sri Lanka. I am not a neutral observer here as I have been involved in a number of applied theatre training programmes across Sri Lanka but particularly in the North and East of the island. There are two points of practice in applied theatre to which Shanmugalingam has rightly drawn attention and criticism. The first is the idea that after a short training programme anyone can run a theatre project. The second is that theatre can be involved in all areas of life addressing issues and improving social problems directly. Shanmugalingam has pioneered theatre training in Jaffna for many years and knows the difficulty he has faced in both maintaining the integrity of his programmes and also support for them. He is therefore rightly critical of the idea that people with limited training can instantly become theatre practitioners. I agree with this point and what his position has taught me is that while theatre must remain an inclusive art form we must remember the theatre in applied theatre. In the UK we have become very good at teaching about the contexts in which theatre can be practised, but at times we have lost sight of the theatre skills necessary to make this happen. The experience of working with theatre colleagues in Jaffna is that the skills of the theatre makers are paramount if the work is to be properly applied. While I still believe many people have the capacity to be involved in theatre projects, Shanmugalingam has taught me that we must not forget the artistry that gives these projects their strength in the first place. Attention to the social issue should not mean that the art is marginalised. Shanmugalingam’s sense of close connection to the context in which he lives demonstrates that his theatre emerges from that context rather than becomes overwhelmed by it.

This leads us to the second concern about the term applied theatre. When social policy networks or NGO’s are desperate for solutions to complex problems, it is easy for them to see theatre as a relatively inexpensive option. Applied theatre was in danger of being that catch all practice that could cure social ills and Shanmugalingam has perhaps rightly criticised the danger of becoming over reliant on these sources of funding. This criticism is all the more pertinent in light of rapid increases of money (such as after the tsunami) or alternatively in light of potential rapid decreases. The problems encountered when theatre artists too singularly following the money is now becoming more widespread in the applied theatre community internationally. Once again Shanmugalingam’s commitment to creating an educational theatre that responds and emerges from its context without being dominated by it could be a powerful vision for applied theatre than ensures both the theatre and the application remained balanced. If applied theatre at its best reminds us that countless people can be actively involved in their communities, Shanmugalingam reminds us that it is the theatre in applied theatre that provides the means and the inspiration for that involvement.

Shanmugalingam continues to inspire countless young theatre makers in Jaffna and beyond. He is a vital figure in Sri Lankan theatre whose work is deeply connected to his place, whose practice has a profound relationship to education and cultural awareness and whose contribution to debates in the arts continues to demonstrate the importance of theatre. He has been phenomenally welcoming to me whilst never being afraid to question and provoke. His challenge has always been done with, what we would call in English, a twinkle in his eye: a sense of mischievous play that underscores the deeply serious conviction he has for the important contribution that theatre can make to society.

James Thompson

University of Manchester

September, 2006